Chicago's South, West Sides have many more cancer patients, less access to care

CHICAGO (CBS) – Chicago has long been a hub for breakthroughs in medicine, but the number of people dying from cancer in the city shows not everyone benefits equally.

For those in Chicago's low-income, predominately Black or Latino neighborhoods, they don't have the same access to or quality of care. CBS 2's Audrina Sinclair examined the problem and who's helping.

From Genella Jones-Riggins' backyard in Roseland, she grows it and cans it.

"[There are] eight or nine different types of tomatoes," she said.

She has stacks and stacks of jars of "shelf-ready food" for at least six months to a year, she said. It's piles of produce.

"It's wholesome food that I grew myself," Jones-Riggins said. "It's my responsibility to make sure that I stay healthy."

Speaking of health…

Sinclair: "Where are you at now in your journey?"

Jones-Riggins: "My prognosis is well. My last scans were clean."

The good news came a year after finding a lump in her breast and having no health insurance.

"You hear all the time about breast cancer, free screenings, but when I needed it, I couldn't find it," Jones-Riggins said. "I called around for two weeks, and I could not find anything."

A friend told her about the nonprofit Equal Hope.

"They made sure that I got everything that I needed," she said.

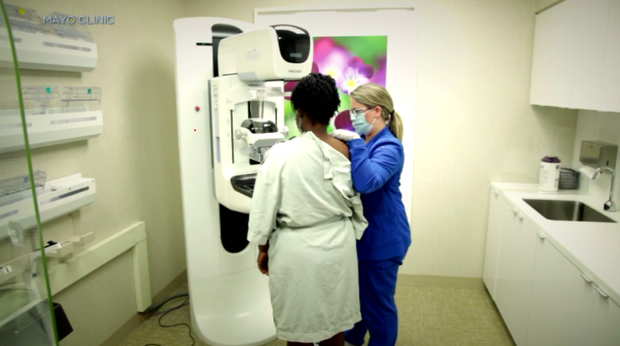

That started with a mammogram and biopsy at Rush University Medical Center, where doctors diagnosed her with triple negative breast cancer.

Sinclair: "Someone went to every appointment with you. How many appointments are we talking about?"

Jones-Riggins: "I had 17 rounds of chemo. MRIs, and you have CT scans, and you have bone scans, and you have bone density scans. Then after chemo, you have radiation and radiation is every single day for four to five weeks."

Her nurse navigator, Rita, was there for her, and the costs were all covered.

"This is a state-funded program that allows women to access care at no cost," said Paris Thomas, of Equal Hope. "Which is why she didn't have to see those bills."

Thomas works to fight Chicago's cancer care disparities with Equal Hope, which helps 1,800 women like Jones-Riggins with breast or cervical cancer.

"We serve the communities on the West and South Side of Chicago," Thomas said. "Primarily those that are Black and brown, and usually those who are considered under-resourced, disinvested in."

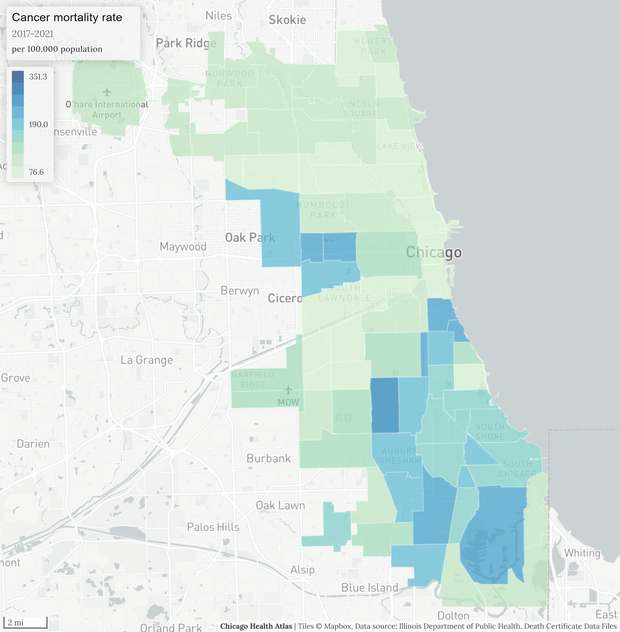

A map from the Chicago Department of Public Health and PHAME Center at the University of Illinois at Chicago shows the neighborhoods where the most people are dying from cancer in Chicago. The darker the blue, the more cancer deaths.

All but one of the communities are on the South and West Sides.

"We know that we have to intervene in this community because there's a problem here," Thomas said.

Equal Hope is intervening for patients treated at safety net hospitals in their neighborhoods. Such hospitals are usually under-resourced facilities with outdated equipment, lower staffing levels, and limited hours.

"Let's say capacity," said Thomas. "Maybe they don't have a full-time mammogram tech, and they're only able to see women once a week. So we know that we now have to pivot and try to move our populations to other facilities."

A study by the Health Care Council of Chicago looked at those barriers to care in the city's under-resourced neighborhoods and found specialists on the South Side are treating three times as many patients as on the North Side. That's about 1,000 patients for every doctor on the South Side of the city, compared to about 350 patients for every doctor in many North Side communities.

Thomas is hyper-focused on the disparities to help people like Jones-Riggins get the cancer care they need.

"I don't know where I'd be without the help that they provided me," said a tearful Jones-Riggins.

To learn more about Equal Hope and its services, visit EqualHope.org.

In the second part of her story, Sinclair will dig deeper into the disparities and ways to tackle them, including a look at a new cancer center coming to Hyde Park.

for more features.